Introduction

A unique definition of a metal is one which has a Fermi Energy (\(E_f\)) in the conduction band. This is one property which gives metals such great conductivity, having an \(E_f\) in the conduction band means that electrons in the valence band can easily move to the conduction band. Unlike in a semiconductor or an insulator in which the \(E_f\) level lies between the band gaps this allows us to be able to model shift in \(E_f\) as a function of filled or occupied electron states.Free electrons in the conduction band can be modeled by what are called Bloch states, the sum of which can be modeled by \(\psi_k(x)=\sum e^{inak}\phi (x-na)\). Of prime importance is what is called the "wave vector" \(k\) which can be manipulated to form Bloch states of varying symmetries. The wave vector \(k\) is associated with the free electrons momentum state, we will examine what is called the "first Brillouin zone" defined as the range \(k=(\frac{-\pi }{a},\frac{\pi}{a})\).

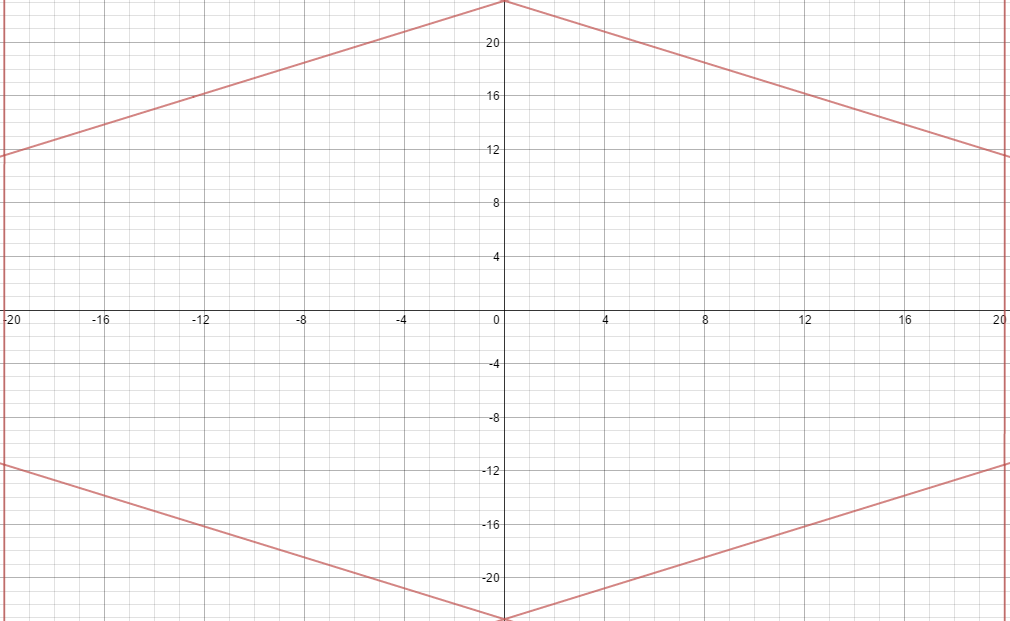

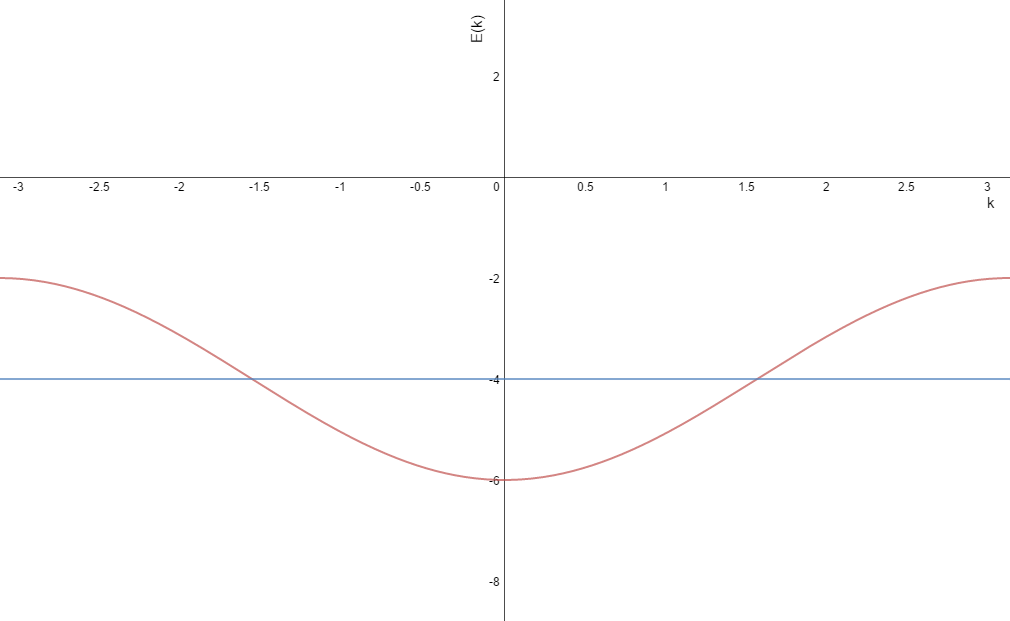

This unique transformation into momentum or Kspace allows us to view what are called "Fermi boundaries" or 2D Fermi Levels as visualized in Kspace. Each Fermi boundary is a line in the first Brillouin zone in Kspace and it is a line of constant energy which separates the filled (area bound inside the contour) to the unfilled states. If we look at the ratio of area within the Fermi boundary as a fraction of the total area in the first Brillouin zone we have calculated the fraction of filled states for a given \(E_f\) with our given lattice structure.

(For brevity of the post the Python code used to generate the animations and diagrams will be linked below, but all that is needed is here.)

Part 1: Simple Cubic Structure

The first structure I will examine is that of a simple cubic lattice modeled by: \(E(k)=E_0-bcos(ak_x)-bcos(ak_y)\). From this equation we can deduce some important properties of this structure. Firstly it is symmetric in the x and y direction because we have both -bcos(ak_x) and -bcos(ak_y)\) contributing equally to the term inside the Cosine function, that is both terms are equal for \(ak_x = ak_y\). Another thing to note is that the lattice constant \(a\) is not changed in either term meaning that the spacing in the x and y direction does not differ.

Lastly we have a range of \(E(k) = (E_0+2b,E_0-2b)\). This is expected for our case as it is symmetric and cubic and we expect the range to be the same above \(E_0\) as below.

This is important as we shall soon see that for varying structures of metal crystals the range of the band width changes.

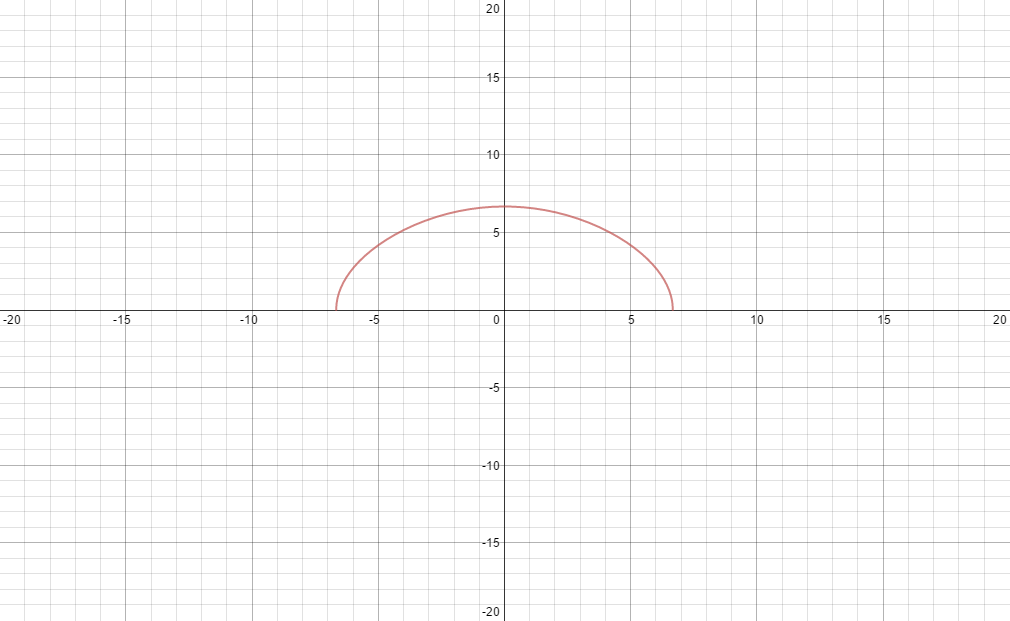

The Kspaces in the animation are well organized into half circles which gradually become more and more triangular. Of particular importance is \(E(k) = E_0 + 0\) this is a special Fermi boundary which I will refer to here as the "prime" energy of \(E_p\). In the plot below the animation \(E_p\) occurs at the center of the graph which is also the point at which the graph switches concavity, it is a point of inflection.

These points of inflection are where the filling of states changes from increasingly more sates per \(E(k)\) to decreasing change in states filled per \(E(k)\).

Visually these points of inflection are of great interested in Kspace diagrams as they are the ONLY Fermi boundaries created with straight lines. In the animation above this occurs where the perfectly straight triangle is drawn at \(E(k) = E_0 + 0\). We will examine more of these special \(E_p\) energies for other crystal structures.

Part 2: Anisotropic Case

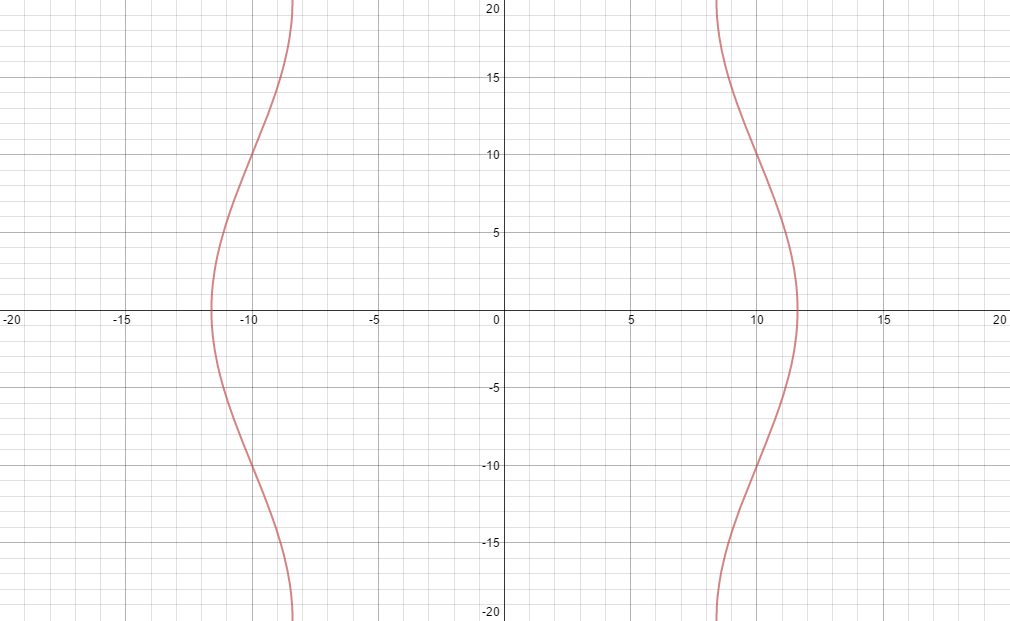

For lattice spacing (ax,ay):

For lattice spacing (ax,2ay):

For lattice spacing (2ax,ay):

In all three cases the graph of States Filled vs \(E(k)\) is exactly the same. The amount of electron states occupied in conduction band of the crystal does not depend on the spacing of the atoms in the crystal but is dependent only on the Energy. In all three cases we reach a Fermi boundary which contains half the total states inside it at exactly \(E(k) = E_0 + 0\), the same as in Part 1.

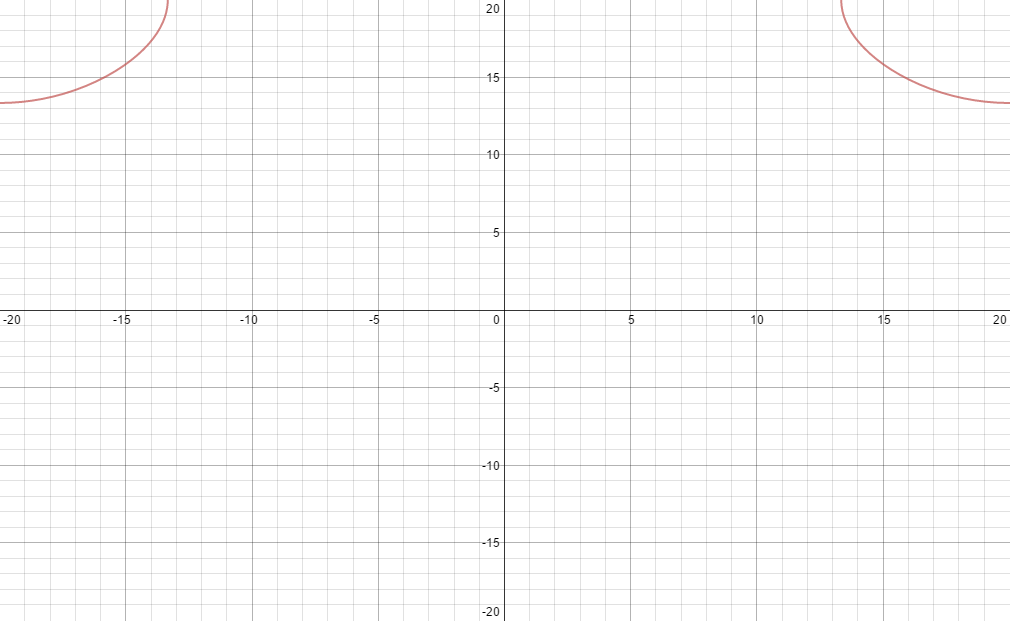

Here the similarities end and we can see that the anisotropic case has some very significant differences to that of Part 1. Firstly we can see that there are four curvatures and concurrently three points of inflection at \(E(k)= E_0 + (-1.5,0,1.5)\).

These are our \(E_p\) values yet with one notable exception at \(E(k) = E_0 + 0\)...in the anisotropic case symmetry has been broken and only some parts of the Fermi boundary formed at these values have straight lines.

There is also now a change in the range of \((k_x,k_y)\) as we no longer have \(E(k) = E_0 + 2b\) or \(E(k) = E_0 - 2b\) as in Part 1. In the anisotropic case \(E(k)\) still ranges in the \(k_x\) direction by \((+/-)b\) but now as we have discussed it only ranges by \((+/-)\frac{4}{b}\) in the \(k_y\) direction. We can then see as the animation and plots above show that the total energy \(E(k)\) ranges only between \(E(k)=E_0-\frac{5}{4}b\) and \(E(k)=E_0+\frac{5}{4}b\).

In essence this crystal structure has a narrower energy band as the energy difference between 0% states filled and 100% is reduced from the simple cubic structure and we need only a band width of \(\Delta E(k) = 2.5b\). This is true even in the case where our lattice structure has \(a_x = a_y\) as we see in the first case above.

Part 3: Complex Structure

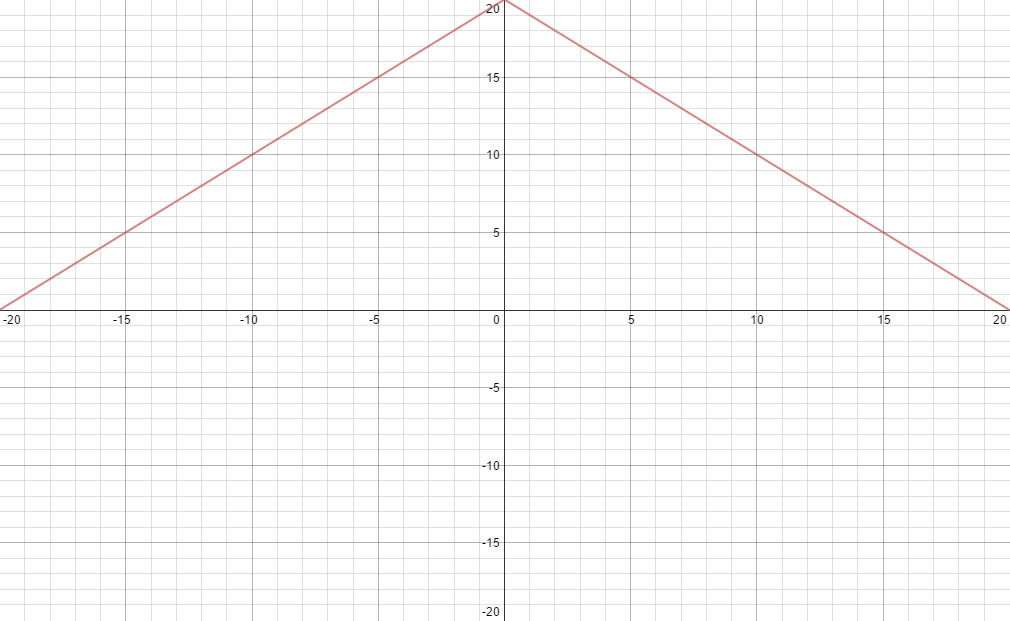

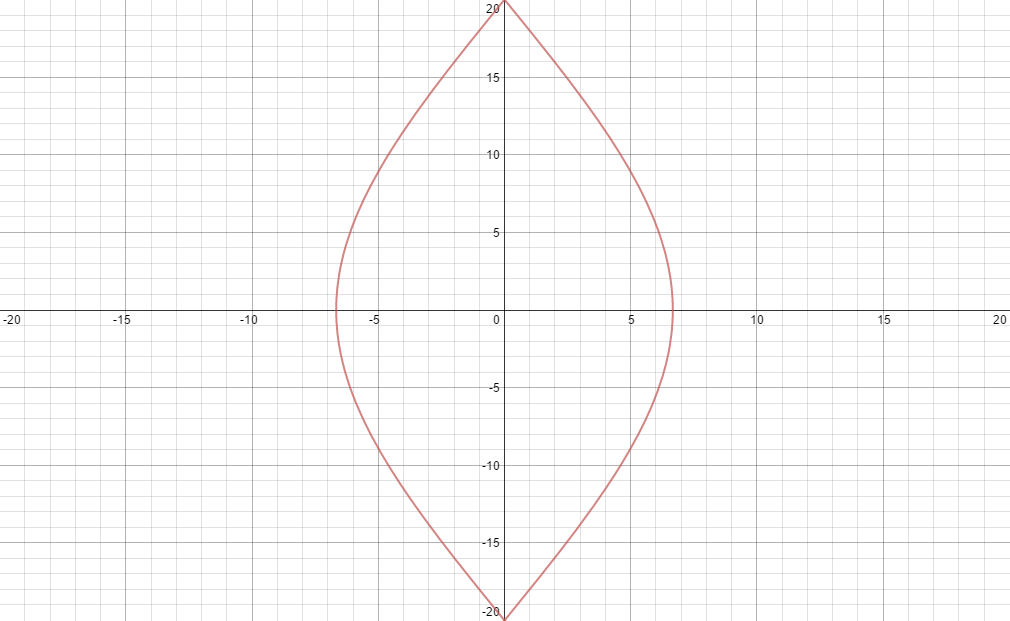

Lastly the case which more closely models a real world metal crystal structure: \(E(k)=E_0-bcos(ak_x)-bcos(\frac{1}2{}ak_x+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}ak_y)-bcos(\frac{-1}2{}ak_x+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}ak_y)\)

This crystal structure also attains a higher compaction of electron states as shown in the plot below the animation. In the plot we can move from \(E_0+1\) to \(E_0+3\) and increase the number of states filled by 40%, the same change in energy in Part 1 would yield only a change of about 22%.

This case and the one in Part 1 have only one inflection point, in our case at \(E(k) = E_0 + 2\) which forms perfectly straight lines angled similarly in a triangle shape but with flat sides forming more of a top half of a hexagon.

Part 3: \(E_p\) and crystal structure

Kspace diagrams have been shown above in deducing the fraction of total electron states occupied in varying crystal lattice structures in a metal, but one can also look at the structure or arrangement of the lattice structure by looking at what I have called the "prime" energy \(E_p\).

In case Part 1 our \(E_p = E_0 + 0\) yields a Fermi boundary which if we look at the entire first Brillouin zone looks like a diamond as shown below:

and in Part 3 we have our hexagonal \(E_p\)

In Part 1 the structure shown is a square at \(E_p\) and this is exactly what we expect for a simple cubic structure, that is one atom surrounded by 4 others on each side. Simple periodic and symmetric about x and y. We can expand our view of the first zone of our function to include nearby neighbor and we can see the simple cubic structure appears as below.

In Part 2 we have \(E_p\) is a hexagonal structure. This is consistent with a more compact structure as we have determined from the data in Part 2. Again viewing the structure at \(E_p\) yields a symmetric period hexagonal structure where each atom is surrounded on each of it's six sides by another.

The anisotropic structure in Part 2 seems rather out of reach visually yet there are some important revelations about its Kspace diagram namely, as we have found, that it has not 1 but 3 points of inflection two of which are special cases where the Fermi boundary satisfies the condition of being an energy of \(E_p\) at \(E(k)= E_0 + (-1.5,0,1.5)\).

For Parts 1 & 3, we have only one\(E_p\) Fermi boundary and concurrently only 1 point of inflection on the plot of states filled vs E. This lead us to deduce the structure of the lattices formed.

So what does it mean to have multiple \(E_p\)? And how can we understand its structure in this case.

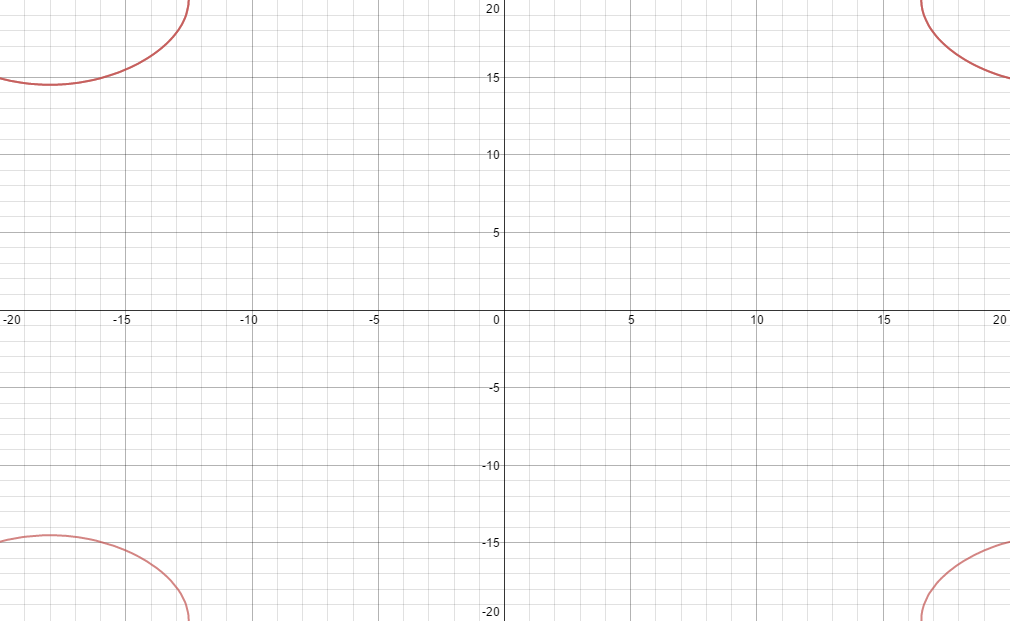

We know that Parts 1 & 3 have only one \(E_p\) Fermi boundary (Diamond and Hexagon respectively) but for our anisotropic case we have the three below:

|

| E_0 -1.5 |

|

| E_0+1.5 |

All but the center graph contains areas where the Fermi Boundary has some linear sections but it is still very distinctly different from that of Parts 1 & 3. If we follow the methods in Parts 1 & 3 it is only logical to determine that for our anisotropic case we have a lattice which is not symmetric or pattern like, unlike in Parts 1 & 3 we can not deduce the structure from only one \(E_p\).

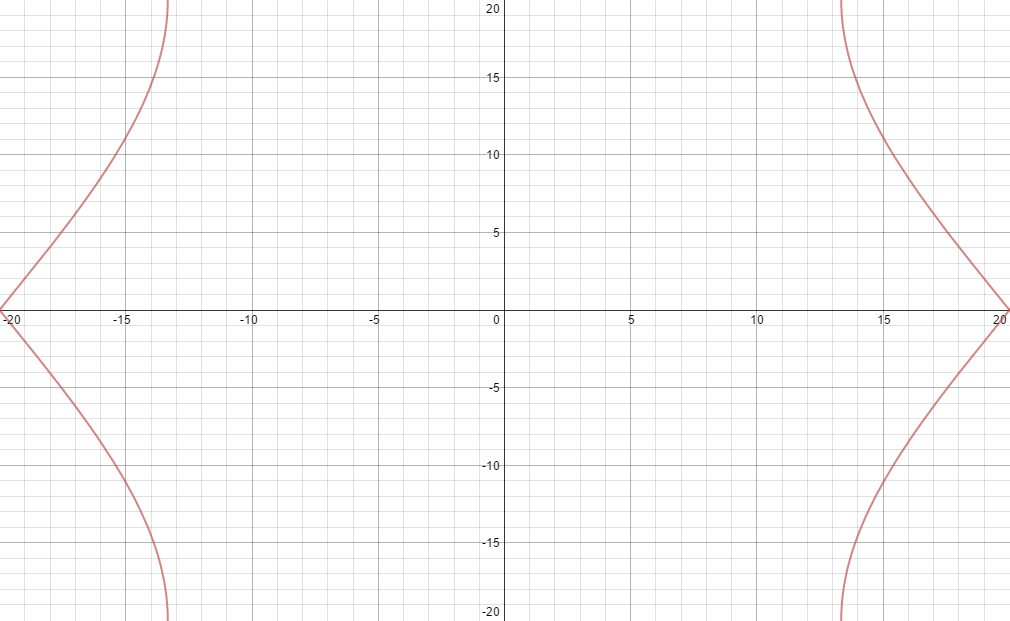

We must then make the conclusion that this lattice structure has a broken symmetry, that is, unlike in Parts 1 & 3 which look the same along any direction, in the anisotropic case we have one symmetry along one x axis and another along the y axis. Below I have expanded out the first Brillouin zone to show the lattice structure in this anisotropic symmetry.

As we have concluded the atoms are arranged in the y direction in rows each almost touching the other but in the x direction this symmetry is broken and a new symmetry takes place, one in which every atom is neighboring two others but not touching or at least not as closely packed as in the y directions.

Conclusion

Kspace diagrams are useful in examining the properties and structure of metal crystals as we have seen in 3 different cases. The cases studied here are very simple and in some cases unrealistic but they nonetheless showcase the usefulness of Fermi boundaries in Kspace for metals.

From the compactness of the electron states and their associated energy band width to the actually symmetry of the crystal lattice, all can be understood from the simple view in the momentum space diagrams of the Fermi boundaries.

References:

http://www2.phy.ilstu.edu/~marx/ph355/Kittel_Solid%20State%20Physics/c09.pdf

http://ucscphysics156-2016.blogspot.com/2016/04/this-may-be-pretty-difficult-and-long.html

http://ucscphysics156-2016.blogspot.com/2016/05/homework-on-fermi-boundaries.html

http://www.wolframalpha.com/